SH: This continues an interview with Mr. William Llewellyn in Hilton Head, South Carolina. This is tape two, side one. Please, continue.

WL: Okay. So, we called Verlin Creed and he came over and we visited for a couple of hours, but he did exactly what he said [he would]. He went back there and, of course, he’d been working with diesel engines on the LCI, and so, he got a job with; what’s the big, yellow building equipment [manufacturer]? …

SH: Caterpillar?

WL: Caterpillar, yes. He got a job with Caterpillar, … and they’re all diesels, and [he was] working on them. He was … the shop manager for Caterpillar Company in Denver. So, he was doing real well. It was fun to talk to him.

SH: For the most part, the crew got along.

WL: … Oh, yes.

SH: You were together for days and days. What did you do to pass the time?

WL: Yes. I played an awful lot of solitaire. [laughter] Oh, I don’t know, you always [find something]. If you’re at sea, you’re busy, but we were not at sea a lot of times. … Mostly, we were on the beach, when we were just waiting around, and so, that let you get ashore, but you’re chipping paint and that’s the way to keep the crews busy, always repainting something.

SH: That was how you kept the men busy.

WL: Yes, yes.

SH: How well supplied were you? Were you ever worried that you were going to run out of something that you needed?

27

WL: No, only I made one mistake one time. … When we were still in the Guadalcanal Solomons area, we were called over [to an area]. … That was when rockets first came in, these banks of rockets they’d shoot, and they had mounted some rocket launchers on some LCTs, [landing craft, tank], which are these big things you called "floating bedpans," [laughter] and they wanted an LCI, … because we have the con and the height to observe and control the things, and have a little demonstration on shooting the rockets on a deserted island off Guadalcanal. So, for some reason, they picked us, I think, maybe, because Gebhart was older, an older skipper. … So, we went in and beached and we picked up Lieutenant General Harmon and Admiral [William F. "Bull"] Halsey, that’s right, he was there, and somebody else, and then, all these captains and colonels were running around, putting chairs under Halsey and the Lieutenant General and everything. … We got on the beach, but, the day before, one of the other LCIs had run out [of gas]. We needed gasoline just for the bow winch and the stern winch, which were gasoline-motor-driven. Everything else was diesel. … We’d been tied up next to another LCI and they were out or something, … so, I guess I gave them our drum of gasoline. … We got all these guys aboard and we’re just starting to pull off and the stern anchor, which we needed to pull off, winch ran out of gasoline. … So, we rushed around and … drained a bucket of it out of the bow anchor winch and got it back there and got them off, but I never gave [away] my gasoline again. [laughter] … Where was I?

SH: You had gone through the Panama Canal, when all the guys got their tattoos. WL: Okay.

SH: Before we move on, when you were at Norfolk, when did you know that you were going to the Pacific? Had you always known that, as an LCI, you would probably end up there?

WL: I don’t remember. … Well, I guess we knew because of the green camouflage we were getting painted [on]. I guess we knew, somewhere along there, that we were going to the Pacific and not [Europe].

SH: When you left the States, the D-Day invasion still had not taken place. [Editor’s Note: Mrs. Holyoak is referring to the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944.]

WL: No, no.

SH: Did you ever think that you might be ordered to Europe, rather than the Pacific?

WL: … No, I think, for some reason, we knew we were going to the Pacific, for … most of the time there, [at Norfolk], and I really don’t know why anymore, but we did.

SH: Did you ever go to any meetings or briefings that dealt with the bigger picture? WL: No, we just had to run the LCI-444. [laughter]

SH: They simply said, "Here are your orders. This is where you are going."

28

WL: Yes, yes. …

SH: Did the orders come in for the LCI-444 as a whole or were they issued to each one of you, such as you as the engineering officer?

WL: Just the ship was ordered, yes. … I was interested [in the fact that], sometimes, [during] the few landings we were involved in, … these Army units would come aboard. … They had these fantastic operations manuals that had been made up for … the job they had to do, you know, … but we didn’t have anything like that. … When their jobs started, ours was over. [laughter] …

SH: You spoke about your shakedown cruise and joining your convoy. Did you participate in any practice troop landings, either at Guantanamo or Florida?

WL: Oh, yes. … Mostly, it wasn’t with troops, but we did a lot of practice beachings and we did them during the summer of ‘43, yes. We did some of them out at Virginia Beach and we kind of would fight for the binoculars, so [that] we could look at girls, sometimes, out there. [laughter] … No, there wasn’t any [troop landings].

SH: You wrote on your sheet that you were in Tulagi, Florida Island, in the Solomons, in December, New Year’s Eve of 1943.

WL: Florida Island in the Solomons. Yes, that’s when we arrived at the amphibious base there. SH: You joined the LCI Flot [Flotilla] …

WL: 22, I think it was. … They sent a guy out, it was kind of a political thing, I think, to be the commander of LCI Flot 22. … That would have been in early ’44, when we were … operating off of New Guinea, and this plump, little guy came along, William, I called him "Wee Willie" (Exton?), William Exton, and he was a consultant, from New York City, in something or other. … Evidently, he had some political connections, and so, he went in the Navy as a commander and they gave him this job as commander of LCI Flot 22. … About fifteen years ago, ten or fifteen years ago, I stumbled [up]on the obituary of William Exton in The New York Times, who had just died at eighty-something-or-other, and it said that he was always very proud of [the] service he’d done in the Pacific as commander of a landing [craft], [laughter] I forget quite how they said it. … Four or five of us were cruising along the coast of New Guinea while William Exton was commander, hadn’t been there very long, and he’d never been to sea before. You know what the score was and we were ahead of him, … going west, and the sun was setting. So, the steam, which is basically steam coming out of our diesel engine exhaust, looks black when you see it in that [light]. So, I happened to be on deck watch and I’m rather sensitive about how my engines are evaluated and the blinker opened up back there and said, "Why are your engines smoking, Com, LCI Flot 22?" and I went down and looked and looked and it teed me off and I thought of a lot of things to say. … I had the signalman send back, "Your engines are smoking more than ours are," and the blinker came back, … "Com, LCI Flot 22, has no engines," [laughter] and so, that was the end of the communication, and then, that night, a few hours later, we pulled into some harbor or other and the blinker opened up, "Captain of LCI-444, come

29

aboard," you know. … So, Gebhart went over and he came back and said, "God damn it, Llewellyn, don’t you ever send a message to the officer on Com, LCI Flot 22, [again]." [laughter] He’d had his rear end reamed for my snotty message. [laughter] …

SH: Apparently, this sense of humor kept you going.

WL: Yes, oh, dear. [laughter]

SH: It took you nearly two months to get to the Solomons.

WL: That was a great trip. That was the trip of a lifetime. …

[TAPE PAUSED]

SH: We were talking about your experiences in the Galapagos.

WL: Yes, and riding with my fellow ensign, … John Wallerstedt. Well, then, I met a Rutgers guy there.

SH: Okay, of all the places to meet someone from Rutgers

WL: Yes, I know, [laughter] and I only met one other Rutgers guy, unexpectedly, and that was, … probably, six months later or so, at some port along the coast of New Guinea. … We were staying a few days, so, we were pulled up on the shore, as we normally were. So, there seemed

to be some construction going on. So, I took a walk, one afternoon, and there was a bulldozer and … I thought I recognized this guy and he was, and I can’t think of his name at the moment [Stan Peters, civil engineer]. [laughter] I could yesterday, but not right now, but he was a civil

engineering student that I knew at Rutgers and he’d gone into the SeaBees, and so, we had a visit there, for a few hours. … That’s the only two Rutgers people I remember, but, anyway, Wally drove the first time and he was right; he’d never driven before. …

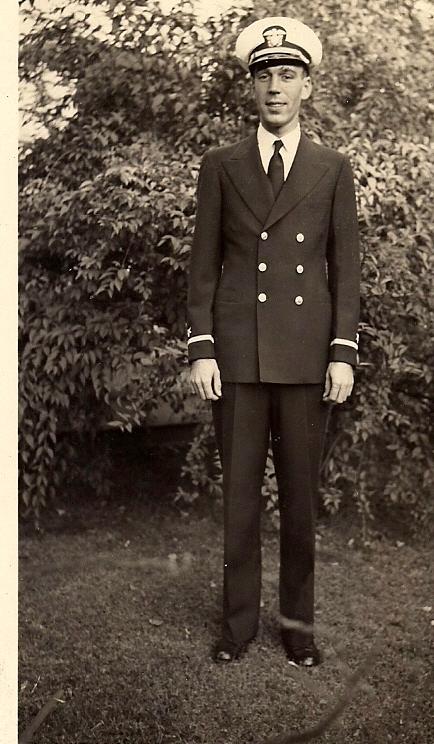

SH: The gentleman who was driving for the first time was your skipper, correct?

WL: No, no. … John Wallerstedt, that’s the picture; yes, that’s it, John Wallerstedt. … Now, when you talk to him; he was kind of a little odd anyway, but I liked him. … Now, when you talk to him, he says, "Uh-huh, uh-huh," and Connie listened to that for a couple of hours and, every time I mention his name, she says, "Uh-huh, uh-huh," drove her nuts. [laughter]

SH: That is amazing, for someone who had never driven before to learn how in the Galapagos Islands, of all places. The fact that Ens. John Wallerstedt had never driven a car before we arrived in the Galapagos Islands has always fascinated me. … But it’s true! I had been driving cars since I was thirteen (whenever my father would let me). Had my first driver’s license when I was sixteen. My first car when I was seventeen. … I thought all my age group probably did the same; at least until John ("Wally") and I went ashore together on November 8, 1943 in the Galapagos Islands! My diary entry for 11/8/1943 reads: "I spent the morning organizing work on the bad engine (piston and liner shot) and in the afternoon I went ashore with Wally to see the

30

sights. There were lots of pelicans, and a seal feeding on some tiny fish by the pier. At the naval base we got a jeep and went over to an Army Air Feld (with a PX) to buy some clothing items. I borrowed the jeep and we drove--just two or three miles, I think--to the air field over a flat, deserted gravel road. When we came out of the Army PX, Wally asked if I minded if he drove and, of course, I said I didn’t. Well. … I no longer remember any specifics but the ride was pretty awful, and when I commented … he told me it was the first time he had ever driven a car of any kind! He told me, in conversations over the years, that he grew up in Kansas City, his father didn’t have a car, he came directly into the Navy from college. … He just never needed to drive! I took over the driving again, about half way back to the base. … And we arrived safely! I think I was twenty-four when all of the happened, and Wally was about two years younger--21 or 22, I think.

WL: … I put this [sheet] together for you. 10/19, we left Norfolk. 10/25, we arrived at Guantanamo. 10/26, we left Guantanamo in a convoy of LCIs and LSTs. 10/29, we arrived at Coco Solo Naval Base. That’s in Colón, on the Caribbean end of the Canal. 10/31, I finally got ashore and spent an evening in Colón and saw all the girls and things, … which I didn’t patronize, [laughter] … though some of my compatriots did, and then, on 11/1, … that was the following day, I went into Colón again, … a couple of us, and we decided to take the train across. So, we took the train across the Isthmus [of Panama] to Balboa and looked around in Panama City and looked around there for a little while, and then, took the train back again. … Then, on 11/2, we were traveling with four other LCIs and the five LCIs went through the Canal. … They’re so small and the locks are so big that they’d put all five of us in one lock, and then, they’d open it up, and then, we’d all proceed to the next one, … and so on, and then, we anchored in the Gatún Lake for a while, before they could let us down on the Pacific side, but it took us all day, that way, to get through the Canal. … You know, when you get to the Canal Zone on the Caribbean side, the tide is about two or three feet, you know, it’s like this, and then, you go through the Canal and you get to the Pacific side and the tide is about thirty feet. … You’re on these docks and you’ve got to have men on the lines all the time, because, if the tide’s going out and you don’t loosen the lines up, why, pretty soon, the thing’s [the ship is] hanging on the dock, you know. So, it was a totally different ballgame on one side than the other. Then, we shoved off on 11/4 for the Galapagos, and then, you have the rest of it there. So, that’s the trip to the Pacific.

SH: Can you tell me about your first invasion, preparing for the operation and so forth?

WL: Well, again, we had a Commander [McD] Smith for a while, in the Solomons, and he took us out at night and had us holding station and [he] trained us. … He was an old Annapolis man that had screwed up, so, … that’s why he was dealing with amphibs, rather than something that

he wanted to be in, but he knew his business. … So, he did a good job, took us on a lot of interesting training cruises. … Then, the first invasion we were on was the Green Island thing, that I showed you the pictures of, … which I think was February 15, 1943, and we loaded up troops, went across to Guadalcanal and loaded our troops, and I think we had them onboard about two days, maybe three. …

SH: Were these Marines?

31

WL: Let me look at that picture. Were they even ours, or were they Aussie Troops?

SH: At one point, you were operating out of Hollandia, but, then, you went to Australia to train with the Aussies.

WL: Yes. These are Aussie troops. I can tell from the helmets. They had the old World War I helmet. So, it was Aussie troops that we …

SH: That you took to Green Island.

WL: To the Green Island [landing], yes, and, as far as I know, nobody shot at us in anger while we were there. …

SH: While crossing the Pacific from the Panama Canal, were you ever worried about submarines? Were you in a large convoy? Did you lose any ships?

WL: … No, no, we went by ourselves and the theory was, "Nobody’s going to mess with us because we’re so small and, if they happen to see us, probably, the torpedo will go under us and won’t hit us anyway." So, we were just, you know, … expendable. [laughter] If we made it, great; if we didn’t, why, it wasn’t any big deal. [laughter] …

SH: How often were you able to get mail in the Pacific?

WL: Mostly, within every month. Yes, I don’t think we went much beyond that before finding an APA [attack transport] or somebody that had a bunch of mail for us aboard it. It worked out pretty well, yes. …

SH: How did you pick up the Aussie troops?

WL: We went over to Guadalcanal and beached, and then, they came aboard there. SH: Had they been part of that operation?

WL: I don’t know, … but that’s where they were. [laughter]

SH: Did you talk with them at all? Did they have any opinions for or against Americans?

WL: [laughter] Oh, they were "one of us," you know. … I never heard [of] any friction, at that time. … No, the main thing was when we went to Cairns, Australia, the next year, for a couple of months on a training thing. … Then, we had the LCI up in the dry-dock for a couple of days, because, when you’re beaching all the time, sooner or later, you mess up your skegs and your

rudders on the bottom of the ship, and so, when we were in dry-dock, why, the enlisted men were living in a barracks where there were a lot of British and/or Australian sailors. … They came back and they said, "These guys are filthy." … You know, the British sailor’s uniform had, I think, a blue kind of shirt or blouse, and then, it came down and it showed a white skivvy shirt, in this area. Well, they said, "Those skivvy shirts were filthy, but they take white shoe polish

32

and paint the part that showed, but they wouldn’t wash anything," and they came back disgusted. … So, that was the main difference. … We tended to be cleaner than some of our Allies.

SH: Where did they house the officers during that training?

WL: Oh, I guess, I don’t even remember, but it was only [for] a day or two. … Yes, I just don’t remember. There’s no story connected with it; I can’t remember it. [laughter]

SH: When you were on Guadalcanal, did you see any of the natives?

WL: … Yes. Well, the Japanese, … there was one or two islands right at the southeastern end of the Solomons group that they didn’t get to. … This Commander Smith that was our flotilla commander at that time had been in the South Pacific in peacetime, earlier, so, he knew a lot of this stuff. So, he took us [there]. … There’s an old German that ran this last little island down

there and had been there for years and he wanted to see him. So, we took a training cruise down there and went ashore and this old German is hiking us through the [island], from one village to the other, and we’re all these young ensigns, think we’re hot stuff. We could barely keep up with the old guy, you know. [laughter] He was in good shape, and so, … as I say, he and the Commander knew each other. … I still have some artwork that they sold there, little statues and bowls and things with inlaid mother of pearl that we bought, that I have a shelf full of them at home, and that’s what they had done, but the Japanese never quite got to them. So, their pads were kept clean, their villages were nice and this German ran a pretty tight island, you know. [laughter]

SH: What was he doing on the island?

WL: I don’t know. … I don’t know whether he sold copra or not, which was the main product of the South Pacific at one time, but … they were making this stuff for sale that a lot of us bought.

SH: He was not a missionary or something else.

WL: No, he just was a trader, I guess, that kind of took over and ended up sort of running the thing, and for the better, because we had another assignment, one time, to go over to [Guadalcanal]. They were expanding an airfield or something and they wanted to move some natives on Guadalcanal. So, they sent us over to pick up these natives and take them about thirty miles down the coast and we took them onboard and I have some pictures of that, but they were filthy [laughter] and there were nursing mothers. … As I say, we had them on about three or four hours, but we hosed everything down pretty thoroughly after they got off. They weren’t very clean or desirable and, other than train and do that, that [mission to] move the natives and the Green Island thing, … that’s about all we did in the Solomons area. … Then, they reassigned us over to New Guinea. So, we went over to Milne Bay, at the very tip of New Guinea, and then, worked our way up the coast, got into Hollandia, I think, probably within a month or so after they’d taken it from the Japanese, which is one of the good harbors on the north shore of New Guinea, and we went ashore there. We found fiber sacks full of rice, all piled up, and a lot of Japanese stuff was still there when we first got there. …

33

SH: What did you do with stuff like that?

WL: Left it right where it was, [laughter] and then, the SeaBees came in and started reshaping the thing and cutting in-roads and building docks and making it a [base], and that was where [Douglas] MacArthur had his headquarters for a long time, before he went up into the Philippines.

SH: Did you ever see MacArthur?

WL: No, just heard about him, [that he] was drinking orange juice and had his wife there. [laughter]

SH: When you went to Hollandia, was the LCI still empty?

WL: … Mostly, we were traveling around empty, yes. … We only got used four times, I think, in there, [the Pacific], yes, where we really were involved with an operation. Oh, we did some stuff in-between, like, when we went from, I guess, … Manus to Leyte, why, … they had, I think, three or four LCIs, and then, there were LCTs, the floating bedpans, who had no navigation equipment. We kind of herded them up. We were their navigation and their support and one of them sank about halfway up and one of the LCIs went alongside to take off the crew. … One of the officers, we understood, wanted to be a radio announcer at some time and he was on the radio. Then, he sounded like an announcer at a football game, describing what was going on, and then, all of the crew of the LCT, they wouldn’t just step from the LCT onto the LCI. They insisted on jumping in the water first, because they heard that if you were rescued like that, why, you got to go home. Otherwise, … you didn’t, necessarily. So, they made sure they got wet before they got rescued. [laughter]

SH: Were they able to go home?

WL: I don’t know the end of the story. [laughter] … Then, another time, … when we were in Subic Bay, why, they sent us out to, what’s the island that the Japanese took in Manila Bay?

SH: Leyte?

WL: No, not Leyte, … the last stronghold, that MacArthur was taken off [of]? … SH: Corregidor?

WL: Corregidor, yes. We went out to Corregidor [laughter] and, again, we were herding some LCTs that were going out, … they’d just taken the island a week or so before, … to take off some of the equipment. … We went along … as navigation and to assist them, if they needed it, and, … really, that’s the only time I ever saw any dead bodies. There were still Japanese bodies kind of floating in the surf on the Corregidor shore when we were there. …

SH: Did you go ashore at Corregidor?

34

WL: I just walked [around] and looked a little bit, not really much.

SH: Did you see any of the caves?

WL: No, I didn’t get into anything. So, we did things like that, but, actually carrying troops, there were only the four times that we really [did that]. …

SH: Would you like to talk about them?

WL: [laughter] Well, let’s see, we covered Green Island. That was Aussie troops and that was no resistance at all. It was just finding it. It was kind of a rocky, little, coral island, and not a beach, so, we found a place to go ashore and let the guys wade in. … Then, the next one, I think, was Noemfoor, which was near Biak, which is kind of in the turkey throat of New Guinea, on the eastern end there, and that was a D-Day. … That was kind of fun, because there were cruisers there and they did a bombardment before we went in and you could kind of see the shells going overhead and, again, we were never actually hit by anything. … I’m not even sure we were ever fired at. [laughter] We were available, if they wanted to, … but that was a D-Day landing, and then, the next one was Halmahera. … When did we go to Australia?

SH: It says here, "10 of ‘44."

WL: October, okay. So, that would have been August or September, … while we were still operating in the New Guinea area, and we did the Halmahera landing. That was D +1, I think. … So, we went in unopposed. The main thing about that landing was that … I didn’t start smoking until I was nineteen, I guess, during finals in my sophomore year or junior year, and I was smoking about three packs a day and I was down to about 135 pounds. … I knew I could never keep smoking if I wanted [to gain weight]. So, I’d been trying to stop and I’d stop for a few hours, and then, borrow so many from our radioman that I’d have to buy cigarettes to pay him back. … When we got to Halmahera, I said, "When we pull off the beach, that’s the end of it. No more cigarettes," and so, fortunately, we got caught by the tide, so, I had an extra six hours before we could get off. … I did throw them overboard and I’ve never smoked a cigarette since. [laughter] I’ve smoked everything else, cigars, pipes, but I don’t inhale those things; … I obviously inhale some. … So, I don’t think I’m doing anything since then to damage my health too much and I seem to be holding together, but that was when I quit smoking cigarettes, finally, at Halmahera. … Then, we went to … Australia and did the training, worked down there at Cairns and came back and rejoined the flotilla, when, in December? in Leyte Gulf, but we missed all the action there, too. … Then, we went through the islands and started operating out of Subic Bay and we did one landing from Subic Bay, which was down on southeastern Luzon, at Mayon. It was the Mayon Volcano. It was just at the base. It was a perfect cone and there’s a Mayon village or something there and that was our last operation. … It was about, I think, maybe a dozen LCIs and three or four LSTs, with their equipment, and a destroyer escort of three or four destroyers. We understood, afterwards, that there were some fourteen-inch guns manned by the Japanese watching us, but they were waiting for the big ships to come, so [that] they never used them, and we were all it was. We were just putting this smaller unit ashore to clean up the area. …

35

SH: Did you ever see any Japanese aircraft?

WL: No. [laughter] War’s fun when you don’t get shot at. …

SH: Would you like to repeat that?

WL: You want me to say it again? I’ve always said that war is the most exciting thing in your life and, if you don’t get hurt, it’s a lot of fun. … The only thing you really worry about [is], you know you might get killed, you just don’t want to get crippled, that’s all, you know, and they’re the guys that pay the price, the ones that … really end up with a crippling injury. …

SH: Did you ever have to take wounded men off a beach?

WL: No, no, never … handled any wounded or anything, no.

SH: Did your ship ever get any R&R [rest and relaxation]?

WL: No. We got that "surprising" trip to Australia, as Wally said when I was talking to him this last time. … That was the only civilization we saw after we left … the States, was when we were in Australia, and we’d just about given up even seeing Australia when, suddenly, they said, "We want two, three boats to go down and train Australian troops," and we were happy to comply.

SH: When you were in the Pacific, did you know what was going on in Europe? Did you know about the D-Day invasion? [Editor’s Note: Mrs. Holyoak is referring to the invasion of Normandy.]

WL: Well, our radioman would tune in [the news], and then, type a little bulletin and he did that almost every day. So, that’s the way we got the world news, yes.

SH: You did know.

WL: Yes, yes, … and I think it was code, in those days, you know. It would be voice, obviously, now, but I understand they don’t even man the SOS band any more. They quit that a few years ago.

SH: That was amazing. I had heard that as well.

WL: Yes.

SH: You mentioned that you returned to Subic Bay and that you were detached from the LCI 444 in April of 1945.

WL: Yes, when we were relieved for reassignment, yes.

36

SH: Where were you going to next? Obviously, the war was still on in both theaters.

WL: … Yes. Well, we got orders to proceed and report, and proceed orders mean that, … in this case, … if it were proceed and report in the US, I think you had two weeks to do it, … from when you got the orders. When it was proceed and report to the US, it meant you had two weeks to report in after you arrived at a US port. … Stella and I had plans to get married as soon as I … got back. So, what I wanted to do was not land at a West Coast port, I wanted to land at an East Coast port, and then, I could visit with my parents for a few days, and then, go get married … in Madison. So, we got on a tanker in Manila, and the Skipper and I were leaving at the same time, so, we were traveling together. …

SH: They replaced only you two on the LCI. Was there anything wrong with the 444? WL: … No. They replaced us. We were replaced on the LCI and relieved. … SH: Your crew stayed.

WL: Yes, yes. As a matter-of-fact, … the night before we were relieved, … it was a nice night. … I woke up and I went out on deck and I could hear some noise and I [was] kind of curious and I walked up. … We were anchored out, I think, in Subic Bay, yes, in Subic Bay; we were not on

shore. … I walked up and, in the boatswain’s locker, up in the very bow of the ship, I looked down in and here’s all of the ratings, the boatswain, the coxswain, the chief motor mac, the signalman, the radioman, all the guys that I knew were down there, drunk as hell. [laughter] I went back to bed and, the next day, I said, "For God’s sake, don’t do that with these new guys." … We had a chief pharmacist’s mate, we had a pharmacist’s mate onboard, and that was his job. He got medicinal alcohol. [laughter] …

SH: He was your corpsman.

WL: Yes. So, that’s where the booze came from. … [laughter] What was I telling you before? …

SH: You were replaced and relieved, but the crew was going to stay.

WL: Oh, yes, yes. So, these … new, other officers came aboard the next day and the ship was turned over to them and we left. … As I say, I told the guys, "Don’t get drunk in the boatswain’s locker for a while, until you know them." [laughter]

SH: What did you and your skipper think that you would be doing next?

WL: We had no idea, no idea. … When we got back, he was reassigned to an LCI, or I’m not sure. He was reassigned to sea duty and for training at Coronado, California, which was where they were beginning to train for the Japanese invasions that never came [about] because of the A bomb. [Editor’s Note: Mr. Llewellyn is referring to the atomic bomb raids on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.] … I was a little disappointed, because I had this engineering degree, and so, they

37

assigned me to the Inspector of Naval Material’s office in Detroit. … So, I was [assigned to] no more sea duty. That was my only sea duty. I was [assigned to] a desk job.

SH: Why were you able to leave the LCI and return to the States? Was it because you had been out in the Pacific for a certain amount of time?

WL: Yes. … I don’t know whether points were involved or not, but I think there was something like that and we knew we’d been out there about as long as [possible]. …

SH: Okay, I wondered if there was a time period.

WL: Yes, they had a rotation system going and we were relieved on that basis. … So, anyway, we got … on a tanker in Manila and that was, supposedly, going to Panama, because we wanted to go through [the Canal] and get on the East Coast. Well, the tanker left Manila and went around and stopped at the Palau Islands, which are; I don’t know, but they’re a little east of the Philippines there, someplace. … Their orders got changed to San Francisco or … whatever, Los Angeles’ harbor, I forget, and so, we said, "We don’t want to go there." So, we jumped off and went to the naval airbase, and then, … there was nothing else going, so, we got on a flight down to Manus, … which was a staging point for the Philippines invasion, down … near New Guinea, and went back there. … The previous time I’d seen Manus, you could almost walk [across] on the ships, a huge harbor and just loaded with ships. [When we] got there, there were about two little boats of some sort there. So, we stayed at the officers’ club there for a few days, … trying to get some transportation, and a tanker came along and it was going back to Aruba and Curaçao, … through the Canal. So, we got on that, but it was still full. So, we had to go to Biak and way up … the eastern end of [New Guinea] to get rid of the oil, and then, finally, we turned around and headed for the Canal and we were, what? I used to know that figure, thirty-one days, I think, out of sight of land, just at fifteen knots, from there to the Panama Canal. So, we got to the Canal and we went through the Canal on this tanker and got off in Colón, and then, went to the Navy … transportation office, looking for transportation for the States. … We got in there and the guy said, "Yes," he said, "there’s a destroyer or something there. You’ve got to hurry to get there. … It’s going to someplace on the East Coast and here’s the name," and we said, "Okay," and we got outside and we looked at each other, the three of us. We said, "Do we want to jump on the boat and go back to the States right now?" and we said, "No, we don’t." So, we wandered off [laughter] and, two or three days later, when we came back, … we said, "You know, we missed that boat," and the guy said, "Yes, sure." [laughter] He said, "There’s a destroyer escort over in Balboa that’s started [across] and it’s coming through the Canal tomorrow. It’s heading for Philadelphia." He said, "You bastards go over there and you get on that thing." [laughter] So, this time we did. We got on the destroyer escort. It had been kamikaze-ed at, where were they kamikaze-ing, up near Japan someplace? [Editor’s Note: Mr. Llewellyn is referring to the Japanese suicide aircraft attacks at the end of the war.]

SH: Okinawa?

WL: Okinawa is what I’m trying to think of, yes, and killed all the officers, because it hit the bridge. So, it was still badly damaged, but, … otherwise, it was okay. So, we … got on this destroyer escort and went through the Canal again. So, I’ve been through the Canal so many

38

times and … I’ve been across the Isthmus by train three times, because I went over and back [the first time], and then, this time. So, we got to Philadelphia … early in the morning and it was foggy and, … as I say, the bridge [was wrecked], … so, they didn’t have much navigation equipment on this thing, and they couldn’t find the end of the channel. So, a fishing boat comes along and [we shouted], "Where’s the channel to Philadelphia?" you know. [laughter] So, they pointed the way and we found the channel, [laughter] and then, … as we went up the river, why, we knew we were back in civilization as we counted condoms floating down, … all over the place. [laughter]

SH: Before we get into Philly, when you were on the tanker, was it a US crew? WL: Oh, yes. It was a US [ship]. …

SH: Military?

WL: No, no, it was Merchant Marine. … By union contract, they had to serve two meats at every dinner, so [that] they had a choice, and we’re thinking, "Boy," you know. [laughter]

SH: Did they share?

WL: Oh, yes, we enjoyed the food, but the Merchant Marine had it pretty good, except in the North Atlantic, when they really had a rough deal. … So, we measured it out; … you know, the tankers had these catwalks that went from one end to the other. So, we knew how many laps was a mile and we jogged a couple of miles every day and [we would] get our tans going. I got back to Madison, Wisconsin, and … I had a tan like it was going out of style, never had one that good since, but, no, it was a nice trip. …

SH: Were you able to get off immediately once you docked in Philly?

WL: Yes, yes.

SH: You then went home to visit your folks.

WL: Yes. Then, we reported in; … did I do it then? I don’t remember exactly when I got my new orders, but, at some point, I did, and then, that was a month’s leave, and then, [I had to] report to Detroit, to the Inspector of Naval Material’s office, which I did around July 5th or 6th, something like that, I think, as I recall the timing. … So, I went up to Plainfield and visited my parents for a few days. …

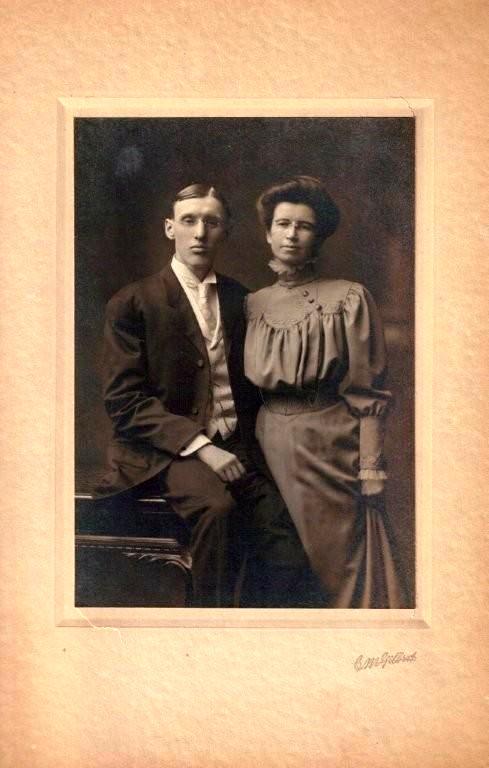

Charles and Emily Llewellyn wedding photo from 1907

SH: Were they able to come out when you and Stella were married?

WL: Yes, yes. We got married on the 23rd or 28th of June.

SH: The 28th of June.

39

WL: Yes, 28th of June. … I hadn’t even seen a woman for over a year and she was a saint. [laughter] … If you’re together every day and working up to this point, and, of course, today, there won’t be any secrets after you get married, [laughter] but it was a different world then. I remember, well, John Wallerstedt was a good Catholic from a good Catholic family, with about twelve kids, I think he said his family had, in Kansas City. … When I first knew him, we were … at Solomons, Maryland. … It was a big room … with cots sprinkled all over and John would kneel down beside his cot every night and say his prayers, and then, when we got on the LCI, for a while, … he and I were in a cabin together and I had the lower bunk and he had the upper one. … I’d be laying there, smoking a cigarette, and he’d be kneeling by my bunk, saying his [prayers]. …

----------------------------------------END OF TAPE TWO, SIDE

ONE-----------------------------------